Published on

At the Texas border, these students help asylum-seekers make their case

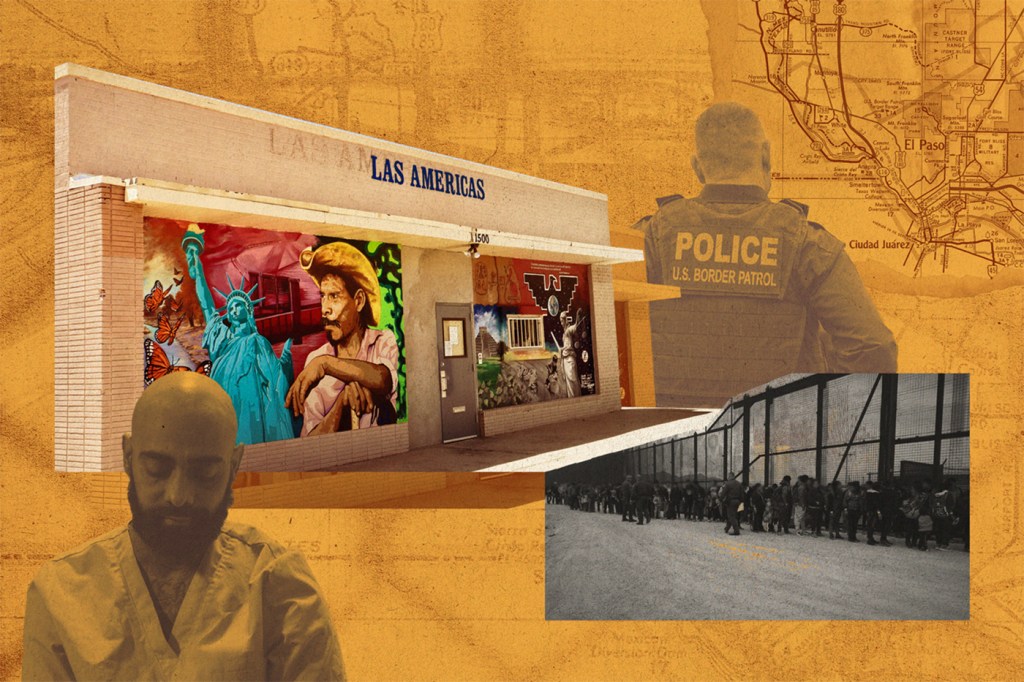

Six Northeastern University School of Law students spent a week volunteering for the El Paso-based Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center.

Nothing prepared Nora Doherty for what she saw at the border.

She came to Northeastern University’s law school hoping to study immigration law. A co-op in Boston had introduced her to how the U.S. immigration system works.

But her May trip to El Paso, Texas, where she met with immigrant detainees wearing orange jumpsuits, separated from her by a glass pane, still shocked her.

“These are people who haven’t really committed a crime,” Doherty says. “The crime they committed in the U.S.’s eyes is having come to the border, but that is the legal way to seek asylum.”

Doherty and five other Northeastern University School of Law students spent a week in early May volunteering for the El Paso-based Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center, which helps detainees in U.S. immigration custody, including many asylum-seekers. The trip gave the students a five-day view into the migration surge at the U.S.-Mexico border, as immigrants from troubled countries such as Colombia, Nicaragua, and Guatemala head north, fleeing persecution, violence or poverty. This year, the U.S. Border Patrol has apprehended or expelled about 200,000 migrants a month who’ve crossed the southern border illegally, outside of official points of entry. That’s five times the typical number of people apprehended per month during most of the 2010s.

For students, there’s no substitute for actually seeing how the border functions.

Ilana Greenstein, a Northeastern adjunct professor and 1998 graduate

This year’s El Paso visit is the third time that the NUSL’s Immigrant Justice Clinic has sponsored a trip to Texas for law students to help immigrants at the border. Like previous trips in 2019 and 2020, this one was funded by donors and led by Ilana Greenstein, a NUSL adjunct professor and 1998 graduate. Greenstein says many Northeastern law students are interested in immigration law—an outgrowth of the law school’s focus on social-justice litigation.

“For students, there’s no substitute for actually seeing how the border functions and working with clients who are going through immigration processing,” says Greenstein. “When I teach, I spend a couple of days talking about border practices, but there’s no way of really understanding it without seeing it.”

Greenstein prepared the student volunteers for the trip with training sessions on the U.S. government’s border practices and asylum law. People can receive asylum in the U.S. if they have been persecuted in their home country, or have a well-founded fear of persecution, due to their race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.

The students then headed to El Paso for five days. There, they worked with Zoe Bowman, a 2021 NUSL graduate who was part of the clinic’s 2019 Texas trip and is now the supervising attorney for Las Americas’ Detained Deportation Defense Team.

“It was really wonderful to have them here in person,” Bowman says, “to make connections with people in detention and provide some time-sensitive legal support to people who otherwise wouldn’t have access to those resources.”

The border agency’s El Paso Sector, which includes New Mexico and two counties in far west Texas, is the busiest of the southern border’s nine sectors, with about 307,000 apprehensions or expulsions between October 2022 and April 2023.

The six Northeastern students worked with immigrants held in two detention centers run by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement: the El Paso Service Processing Center and the Otero County Processing Center, just across the state line in New Mexico. Some of the detained immigrants are seeking asylum, with which the students helped. Others are being held for other reasons, and the students interviewed them to see if Los Americas could help with their cases.

First, the students talked to detained asylum-seekers over the phone, asking them why they fled their home countries. Then they prepared documents to help the clients in their court hearings: affidavits summarizing their stories and reports on conditions in their countries, to corroborate their statements about why they fled.

Asylum-seekers at the U.S.-Mexico border are typically vetted in rapid hearings known as “credible fear proceedings,” Greenstein explains, in which the government “assesses whether the person might potentially be able to make a claim for asylum.” If denied, an asylum-seeker can ask an immigration judge to review the decision. Those who fail at this stage are typically deported. If approved, an asylum-seeker can remain in the U.S. while awaiting a full consideration of their case, which might take months or years.

Doherty, who speaks Spanish, interviewed a woman from Colombia who sought asylum with her wife, claiming they were persecuted at home for their same-sex marriage. (Though Colombia’s constitutional court legalized same-sex marriage in 2016, Colombia remains one of Latin America’s most dangerous countries for LGBTQ people.) The client also reported a long history of abuse in her family.

“We probably spent a couple hours on Zoom,” Doherty recalls. “I was trying to hear her story and write it in a clear, concise way, so the judge will see how it’s tied together.”

The students spoke to recently detained people in the detention centers, in person and by phone, to conduct what Las Americas calls “intake” — the nonprofit’s process for learning why people are in immigration detention and whether the organization can help them.

At the El Paso detention center, Doherty interviewed a Mexican woman who said she was seeking asylum because of abuse by her children’s father and a Dominican businessman who said he’d fled gang extortion. Blessing Eyee, a law student from Nigeria, interviewed several detainees by phone, including a Nigerian man who said he was in danger at home because he supports an independent country for his homeland’s Igbo people.

“When you listen to their story, you will know someone that has a genuine reason for seeking asylum, and someone that is just making up stories to enable him or her [to apply] for asylum,” says Eyee. In the Nigerian man’s case, Eyee’s research into the conditions in her home country confirmed much of his story: he’s affiliated with the Indigenous People of Biafra, a group that the Nigerian government has, controversially, designated as a terrorist organization.

Later in the week, the students spent time in immigration court, observing how the judges handled a day’s worth of detainees’ cases. They watched the detainees represent themselves in court, without attorneys, while struggling with language barriers. “It felt like a very unfair process,” says Doherty. “The government has an attorney who’s there all day, saying, ‘Yep, we should deport this person, this person,’ and the detainees are defending themselves. It just felt very skewed.”

Bowman says Los Americas has agreed to represent several immigrants whom the Northeastern students interviewed. But the Colombian woman whom Doherty helped was denied asylum, first by an asylum officer, then by a judge who, Bowman says, grants asylum in only 3% of cases. She’ll be deported. Her wife, by contrast, was assigned a different asylum officer, who granted her permission to stay. She has been released into the U.S. and has been given a long time to make her asylum case.

“There’s a huge amount of arbitrariness about what happens at the border,” says Bowman, who argues that the speed of the “credible fear” hearings process makes it hard for migrants to prove that they face persecution at home. “People often get rapidly deported back to their home countries without a real chance to fight for their case.”

Asylum officers with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services heard more than 93,000 credible fear cases in the 12 months between June 2022 and May 2023, and granted permission to stay in 63% of cases, according to the agency’s most recently reported figures. Immigration judges overturn about 25% of asylum officers’ denials, according to an analysis by Syracuse University.

Another asylum case that a Northeastern student worked on has had a mixed result so far. An Afghan immigrant who said he was in danger of persecution by the Taliban because family members had worked for Western companies was denied asylum. But, he was released into the U.S. and is living with family pending his appeal.

The students left El Paso with hard-earned lessons and valuable experience. Blessing says she felt fulfilled to have helped detained defendants who otherwise “don’t have anybody to help them.” The experience, she adds, “actually boosted my confidence that even if I graduated today, I’d be able to carry out in real life all that I’ve learned from my immigration class.”

Doherty agrees. “I think it’s going to help me no matter where or what I end up doing,” she says.

But she left El Paso concerned about how the U.S. treats migrants who come to the border.

“We’re a country that bases ourselves on justice, a system that feels fair and equal,” Doherty says. But after seeing the obstacles that detainees face as they try to make their case before immigration judges, she considers the process inherently unequal. “It feels like whatever is happening now,” she says, “isn’t as just or equal as we are pretending it is.”

Erick Trickey is a Northeastern Global News Magazine senior writer. Email him at

e.trickey@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @ErickTrickey.