Published on

How Northeastern student-athletes become champions on field and in classroom

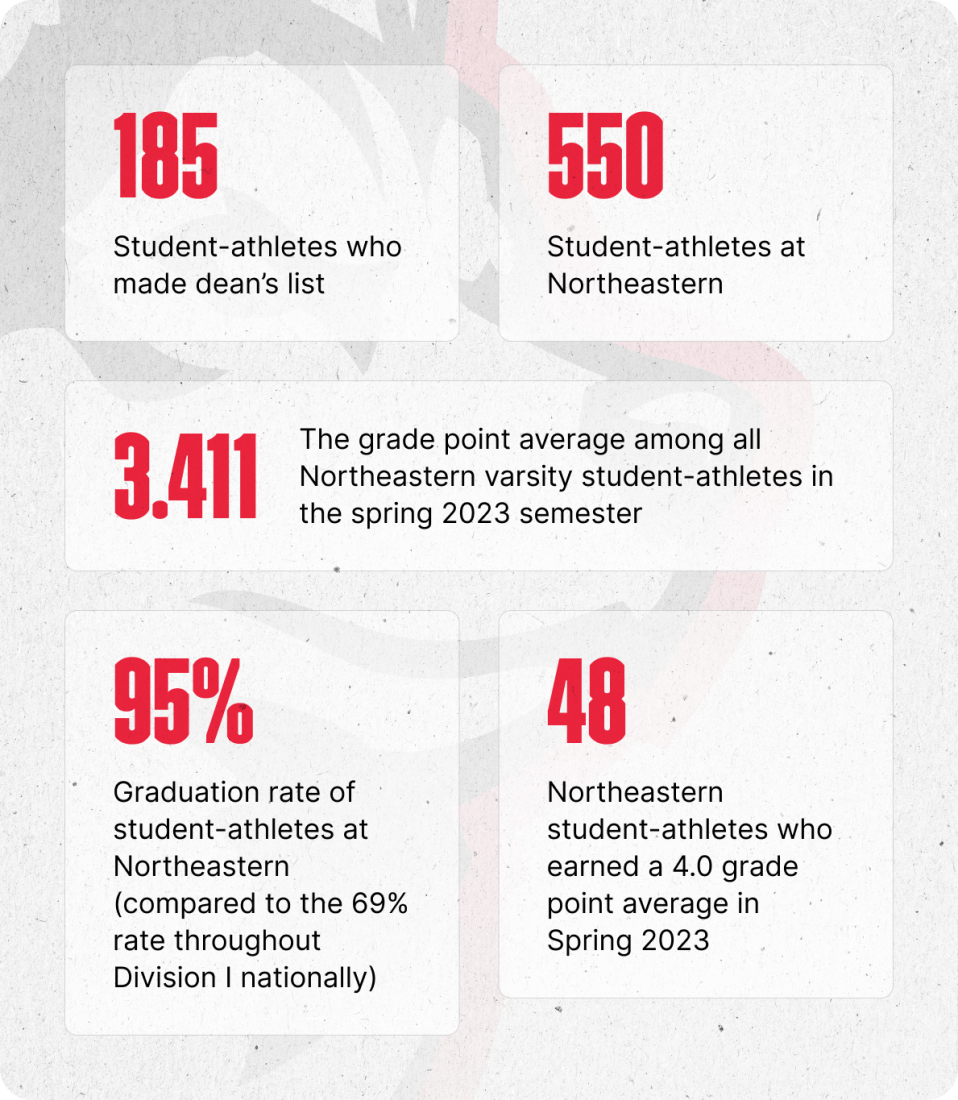

They averaged a 3.411 GPA this past spring while also boosting the university to a No. 11 national ranking for athletic success. “I think people may not realize the demands that are on our student-athletes and how hard they work at both of their crafts,” says Jim Madigan, Northeastern’s athletic director.

Gregory Bozzo crouches for half of each baseball game beneath a coat of armor — mask, vest and shin guards — that helps only so much against tipped foul balls approaching 100 mph. As the catcher on Northeastern’s baseball team, Bozzo is responsible for managing the pitchers, throwing out base stealers, making small talk with umpires and swinging the bat himself.

“There’s a lot that goes into the position and that’s why I love it so much,” says Bozzo, a 6-foot junior from Basking Ridge, New Jersey. “You have to know how to manage the game within the game.”

It’s the least important of his two full-time jobs at Northeastern — contributing to a baseball program that has reached the NCAA tournament two of the past three years.

Bozzo’s second job, fulfilled in private, away from the public eye, is to earn a business administration degree that will set him on a path of lifelong success.

At Northeastern, those academic and athletic goals are braided together.

Athletically in 2022-23, Northeastern ranked No. 11 in its category of Division 1 schools that don’t compete in football. That recognition was driven by four conference tournament championships by Husky teams in addition to three NCAA team appearances that included a Frozen Four berth in women’s ice hockey.

Classroom performances were even more impressive. The grade point average among all Northeastern varsity student-athletes this past spring was 3.411 (up from 3.324 in the fall), marking a seventh straight semester above 3.3. (A national ranking of student-athlete grade point averages is not available because academic rigor varies so greatly from one university to another.)

At Northeastern, 185 student-athletes made dean’s list, and 97 achieved “Top Dog” status with a grade point average of 3.8 or better.

“I think people may not realize the demands that are on our student-athletes and how hard they work at both of their crafts,” says Jim Madigan, Northeastern’s athletic director. “Our student-athletes have a skill set to compete in their sport at the highest level — and at the same time, when you see they have an average GPA of better than 3.4, it’s impressive because they really are balancing two full-time jobs.”

While Bozzo was organizing a pitching staff that ranked third nationally in earned run average (3.75) on the way to earning a Northeastern-record 44 victories this season, he was also maintaining a 3.5 grade point average. Huskies baseball coach Mike Glavine calls Bozzo “a great ambassador of what it means to be a student-athlete at Northeastern.”

Several of Bozzo’s teammates are also business majors, enabling them to help one another with homework in a way that deepens their bond.

“I love school but I’m not going to lie — there’s nothing I’m more proud of than to say that I can go out there and catch for the 40 guys behind me,” Bozzo says. “It’s an amazing, amazing feeling.”

The urgency of competing in the moment — in the pool or on the field or ice — is balanced by the long-term investment in schoolwork. The yin-yang relationship between athletics and academics is all about “immediate gratification versus delayed gratification,” says Bill Coen, the winningest men’s basketball coach in Northeastern history.

Expectations continue to grow at both ends of the university spectrum, says Madigan, who was a player on the breakout Northeastern hockey teams of 1981-85 that won two Beanpot titles and reached an NCAA Frozen Four.

“The demands are much greater on our student-athletes than they were even five or 10 years ago,” says Madigan, who revived the men’s hockey program as coach from 2011 to 2021. “Northeastern keeps getting stronger academically and we’re attracting better student-athletes.”

The coaches of Northeastern’s 17 varsity teams are charged with developing their student-athletes in both worlds.“My message to recruits always is, ‘Your priorities are family first, education second, hockey third and then your social life is a distant fourth — and if your priorities are in that order, we’ll get along great,’” says Dave Flint, the reigning national coach of the year in women’s ice hockey. “You’re getting an opportunity to get a degree from one of the best schools in the country. You need to take advantage of that opportunity and make the most of it.”

Homework at the Olympics

Alina Mueller, who recently finished her ice hockey career as the Huskies’ all-time leading scorer with 254 points in 159 games, is one of the greatest athletes to compete for Northeastern.

Mueller was a top-10 finalist for the national player of the year award for an unprecedented five straight seasons. In 2014 she became the youngest women’s ice hockey player to medal in the Olympics — scoring the bronze-clinching goal for Switzerland as a 16-year-old — and she routinely ranks among the leading scorers at the Olympic and World Championship tournaments.

A secret of her success is self-discipline. During her last two Olympic appearances in South Korea and China, she spent hours in the Athletes Village fulfilling her coursework obligations for Northeastern.

“Obviously, I tried not to do any homework on the days we had games,” says Mueller, who sought to do most of her homework during the team camp that precedes the Olympic or World Championship tournaments. “In the pre-camp we practice twice a day or we would have two [events] with the team. And then the rest of the day I would do schoolwork.”

Mueller, who is completing a master’s degree in human movement and rehabilitation sciences, says she graduated with a grade point average of “3.68 or something” — which she half-dismisses as being “alright, I guess.”

“Yeah, it’s ‘alright,’” says Flint, laughing. “She was majoring in behavioral neuroscience.”

The stress of achieving in the classroom was harder on Mueller than anything she faced on the ice.

“The only time I felt really overwhelmed was definitely because of the academics,” she says. “It was mostly during exam periods, like finals week, because our season was still going on.”

Flint says his teams appear to lose focus at practices around major exams — which makes the Huskies’ ongoing record of six straight Hockey East titles all the more impressive as the tournament coincides with spring midterms.

“They’re bombarded — they’ve got papers, they’ve got tests, they’re all stressed out,” says Flint, whose team earned grade point averages of 3.36 over the past two semesters. “So those weeks I try to make practice fun and maybe a little shorter.

“But I’ve also had kids come in freaked out because they have all this work to do. And I’ve said, ‘Hey, take today off, go do schoolwork if it will make you feel better.’ If I’m preaching that school is more important than hockey, then I can’t sit there and say hockey is taking precedence over school here. Missing this practice isn’t going to be the end of the world, and if it helps them academically, then that’s more important.”

Academic success is driven in no small part by Student-Athlete Support Services (SASS), a program of academic, career and personal counseling at Northeastern. Incoming student-athletes who may struggle at Northeastern are identified and often encouraged to enroll in summer classes to get a head start.

Tutors are available for every Northeastern team. SASS counselors David Brown and Joseph Flynn took turns traveling with the baseball team this spring.

“It’s not just all baseball when we’re on the road,” says Glavine, whose team averaged grade point averages of 3.38 in the fall and 3.23 during their record-setting season in the spring. “We’ll have one or two study halls during the day and there’s downtime at the hotel, on the bus or at the airport. Having that academic adviser there really helps.

“Joe and Dave are part of our team,” adds Glavine. “They’re fully invested in what the guys are doing on the field as well. They’re with us when we’re practicing, when we’re working out, when we’re at the games. They’re on the field helping out wherever they can to make our lives a little easier.”

The three eights

Coach Roy Coates’ women’s swimming and diving team is typically the most successful academically at Northeastern. This spring Coates’ program led the athletic department with a team GPA of 3.69.

“I believe you can have excellence in most facets of your life and I think that’s what our women are looking for,” says Coates, who has been coaching at Northeastern for 30 years. “They’re looking for excellence in everything — academics, social life, athletics. They’re just those kinds of people.”

Virtually all of Coates’ training regimens — academically and athletically — have life lessons built in.

“You want to be a great swimmer or diver,” Coates says. “But you also want to pursue these very strenuous academic requirements at Northeastern. How do we have that balance?”

Time management becomes a crucial lifelong skill for all student-athletes at Northeastern. NCAA rules limit practices and competition to 20 hours per week, but athletes tend to spend additional hours training individually — which does not account for the hours devoted to visualizing and dreaming about the competitions to come.

With respect for all that they’re trying to accomplish, Coates refuses to browbeat his athletes.

“I’m not going to yell or scream,” he says. “I’m assuming you want to get better. And if you don’t want to get better, then you don’t have to be on my team.”

A key metric for Northeastern swimmers and divers is what Coates calls “the three eights.”

“We ask you to try to get eight minutes of meditation in a day, eight hours of sleep at night and eight glasses of water during the day,” says Coates, who includes weekly mental training as part of the team’s repertoire. “I’m not saying we all do that. But if you can get those things in your life, you’re going to recover better, you’re going to be fresher and you’re going to be more focused than you would be otherwise.”

The degree is non-negotiable

Madigan notes that smarter athletes often have an edge over the competition. “When you look at who are the best players on a team,” he says, “most of those people are also among your best students.”

Coen has found that to be true during his 17 seasons at Northeastern.

“The game is more than 50% mental,” Coen says. “If you’re an elite decision-maker, you’re going to be a good player, and I don’t care what sport it is. And the same is true in life. If you want to be successful in the classroom, you have to be able to critically think and analyze stimuli and data and make the right choices.

“There’s a saying in sports, and particularly basketball: How you do anything is how you do everything.”

When Coen visits men’s basketball recruits, classwork is a point of emphasis.

“The way we present this opportunity is that we’re an elite academic institution that is trying to be elite in basketball,” Coen says. “So right away it strikes a tone of how important academics are to everybody involved in the athletic department. And then you reap what you sow — you attract serious-minded students who want to be great in athletics. You’re getting high-character kids who want to be elite and who are disciplined and consistent in their effort.”

A pillar of Coen’s program is Caleb Donnelly, a 6-foot-1-inch guard who walked-on to the men’s basketball team a decade ago.

“Caleb was a man with a plan,” Coen says. “He was an A student in chemical engineering—right up there with the very best of any Northeastern students—and he was the most disciplined and efficient young man. Every minute was accounted for. He had a daily plan and he just attacked it.”

Donnelly earned a basketball scholarship and contributed 13 points in the Colonial Athletic Association championship game to help Northeastern earn a bid to the 2015 NCAA Tournament.

“His discipline and his perseverance were on display for everybody,” Coen says of Donnelly, who in 2021 launched the hedge fund 93North Capital. “He wasn’t the most gifted or physically talented young man that’s come through. But by far he was the most disciplined and purposeful in his time here, and he was an inspiration to everybody in the program.”

Men’s basketball programs throughout Division I have been affected by name, image and license (NIL) payments to student-athletes and a transfer portal that enables them to move from one school to another.

“I still believe in the collegiate model,” Coen says. “This is a transformative time in young people’s lives. You’re trying to find what you’re good at, what you’re passionate about, and the education model here at Northeastern with experiential learning is built for that. It’s part of our DNA as a university and it’s a huge selling point in the recruiting process—that practical, pragmatic model of education.

“You might not win a championship and you might not be an NBA player. But what is non-negotiable is that you get your degree so that you can support yourself and your family. It’s the persistence and perseverance that’s going to carry the day, and the grit of every Northeastern student is out there on display all the time, whether it’s in the classroom or on the court.”

Ian Thomsen is a Northeastern Global News reporter. Email him at i.thomsen@northeastern.edu. Follow him on Twitter @IanatNU.